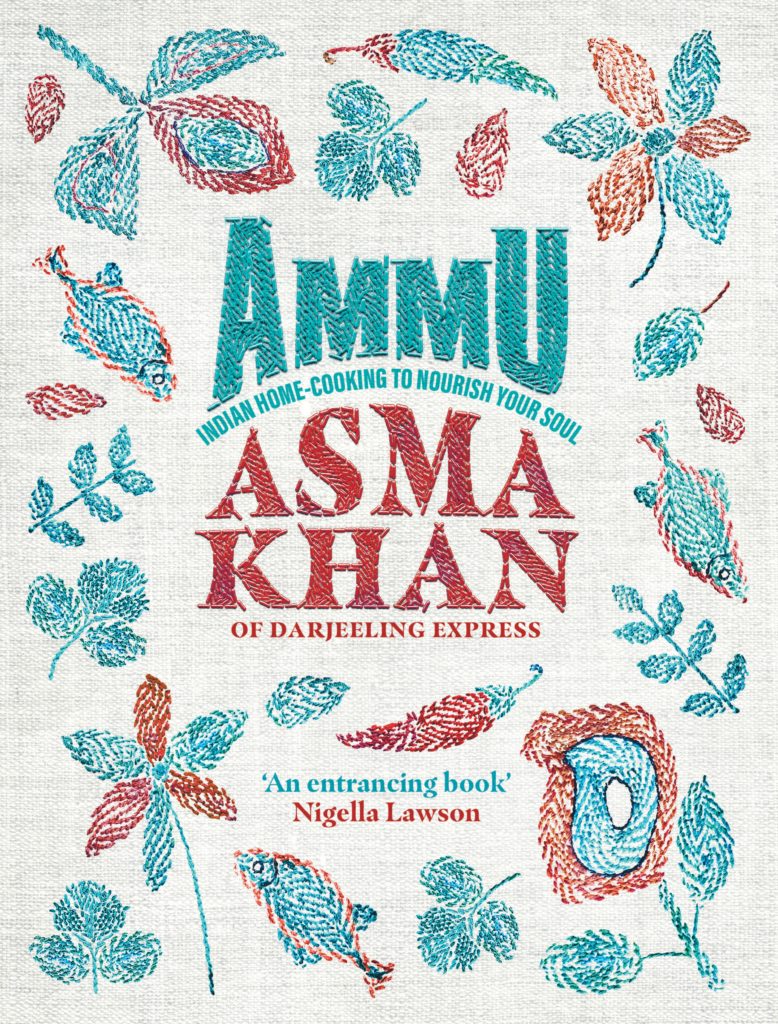

Asma Khan’s latest cookery book, Ammu is a delightful collection of childhood recipes that celebrates the power of home cooking and the inextricable link between food and love. Published by Ebury, the book features more than 100 recipes alongside a wonderful memoir which captures Khan’s childhood and the woman who taught her how to cook, her Ammu.

It is mid-March – about a week before Khan’s launch – when I’m able to schedule an interview with her on Zoom. I’ve been sent the book in advance and have spent days salivating at each and every recipe. It’s funny because while I have shelves of cookbooks, there’s nothing like this one, something that transports me to my childhood, reminds me of the dishes my Mum used to make. I instantly fall in love with most of the recipes – there’s everything from chicken biryani to zarda, and while I don’t quite have time to try and test one ahead of our chat, I am buzzing with questions. Khan is notoriously busy – a chef who famously heads up Darjeeling Express I’ve been told I only have fifteen minutes and I’m keen not to waste them.

What strikes me about Ammu is the desire for connection – to home, to family, and the comfort of food you ate as a child. In the days leading up to our chat I wonder if the project was conceived during the pandemic, at a time of heightened social isolation. It’s something I’m keen to ask Khan as she appears on my screen.

“I always wanted to write this book,” she tells me. The pandemic was devastating for her. Not only was she thousands of miles away from family back home but early on but Khan sadly lost three members of her family to Covid-19, and suddenly the place she grew up was very different.

“I didn’t want to write this book after Ammu,” she pauses. “I wanted her to read this book, I wanted to the book to be in her lifetime and I knew the book would take long.”

Khan’s community was shattered, friends lost their parents, her time was filled with grief and worry. At home, with subsequent lockdowns her restaurant was forced to close, Khan found herself in huge debt with all the responsibility of keeping afloat. “Suddenly everything stopped and I thought this is the time. This is my opportunity. I’ve been shown the door of how I can write this book.” Looking back, she says writing the book probably kept her sane. “It kept me steady because I was extremely anxious about not being able to see my parents and I couldn’t travel.”

“There’s something universal about food memories – they linger somewhere hidden in your soul. Just as the sound of raindrops, the lyrics of a song or the feel of a fabric can transport you to another world so with food. The memories flood back. They take you home.” ~ Asma Khan

We move on to talk about the writing process. It feels slightly counter-intuitive to me, I tell her, to figure out how a dish is made, especially one cooked by our mums because they never seem to care to measure anything. “My mum was exactly like your mum,” she smiles. “You can’t be a South Asian mum if you actually give instructions. That’s below you. My mum’s also completely random – put this, put that and the puts ten things and doesn’t tell you want she’s put in.” And that’s the beauty of a cookbook such as this, it can be the starting point of unravelling the mystery of how Mum made it.

Khan said that it was this mystery that made it difficult to write the book. Her first step was to start in the kitchen and intuitively cook each dish – relying on memory and taste, to figure it out as she went along, to think back to the spices and various processes used. She admits that when she began she didn’t measure anything at all – she says it’s not how she cooks, preferring to cook by andaaz – a process that relies on the hand and eye. It was only later when she was happy with the dish did she recreate it, using exact measurements.

“That’s why the book is invaluable,” she says. And I agree. I am looking forward to making it just like mum because I finally have a useful starting point.

Each chapter of the book is beautifully weaved with an intimate insight into Khan’s roots and culture; from her early life growing up in India to her arrival in Cambridge as a young bride, and later becoming an ammu herself. I ask Khan about what it was like to revisit her childhood for the book, to unearth memories and reflections. She explains that the process was particularly painful. “I cried a lot. I wept. I listened to a lot of music. I couldn’t sleep. I felt quite uprooted again. I felt this when I moved to this country thirty years ago. The sense of fear, of longing, of feeling disconnected from everything. I had this again during the pandemic.” She stops to acknowledge that this was a shared sentiment by people all over the country. “I was writing about places that I knew I could never go back to again. My childhood homes, my people in the book that are no longer there.” Khan says she wanted to write the book with honesty and it is this sincerity that leaps off the page. “I didn’t want to cover up, hide my wounds and my scars. I wanted to tell it as it is.”

Ammu is published by Ebury and is out now.