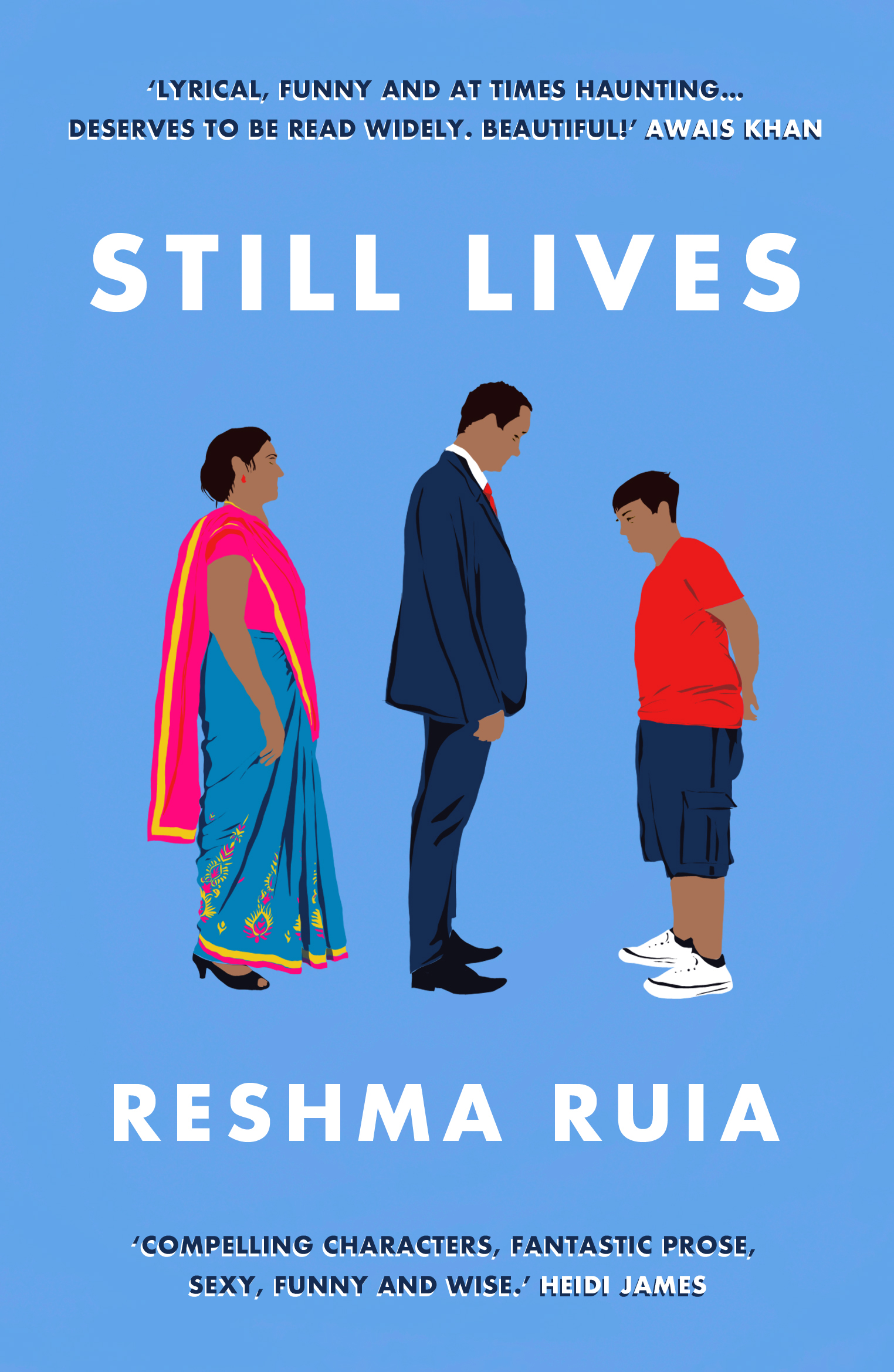

In this exclusive feature for The Asian Writer, Selma Carvalho and Reshma Ruia discuss Ruia’s latest novel Still Lives which explores, with complexity and nuance, a life in crisis.

SC: The protagonist of Still Lives, PK Malik is a first-generation Indian immigrant, trapped between modernity and tradition, between desire and restraint, between personal fulfilment and conforming to community values. What made you write a novel set in Manchester?

RR: The Indian community in Manchester is a strong, vibrant presence that reflects the historical links between Britain and India. It is commonly thought that Manchester’s South Asian community developed during the 1950s when people came from countries including Bangladesh, Pakistan and India, as textile workers to work in the mills. My father in law came here in the late Fifties, sensing an opportunity to trade in textiles. Manchester was the engine of industrial growth and has a strong, welcoming entrepreneurial spirit that persists till today. I wanted to set my novel in this city because I wanted to celebrate this spirit of resilience, openness and dynamism that has attracted not just South Asians, but also the Caribbean and Jewish community.

SC: PK’s affair with the Jewish Esther Solomon takes centre-stage. Esther, in a moment of introspection says, PK and she are bound by ‘the same neurosis about being on the margins.’ Very few Jewish characters inhabit Asian writing, but of late, I often hear the sentiment that the Indian and Jewish diasporas are very similar. What made you take the bold decision of crafting Esther and what do you think is the shared ideological space between Indians and Jews?

RR: It would have been easy for me to find a love interest that was also Asian, but I deliberately chose a Jewish protagonist because I wanted to highlight the similarities that bind the two diaspora communities. Immigrant communities-particularly first generation carry within them an undercurrent of anxiety and nostalgia. They may have trappings of material success, but they are always aware of their ‘peripheral’ status within the host society. A fear of failure and rejection looms over my novel as does the elusive sense of ‘belonging’ and ‘otherness’. Esther refers to Israel as ‘the mother country’ and PK has a stubborn sense of defiance and determination in being a successful ‘model minority’ who cannot return to India as a failure. Moreover, both communities have a strong sense of family and their cultural identity and heritage shapes their response to the world around them.

SC: PK has a vision of life in the UK which is entirely different to that of his wife, Geeta, for whom the mango becomes a metaphor for India. While PK is assimilated, a man who sees success as the pathway to fulfilment, Geeta is emotionally bound to the idea of India, guarding her origin story as that which defines her, and yearning always to return to the motherland. You have skillfully juxtaposed the immigrant quandary, whether to assimilate or to hold onto the past. As we watch the Tory leadership race unfold, with the possibility of Rishi Sunak emerging as the prime-minister, what are your thoughts on assimilation versus community?

RR: ‘Where do you come from, originally?’ I have become so familiar with this question and it does not perturb or annoy me in the least. I am proud of my Indian heritage and cultural DNA. This does not mean that I lock myself in a silo or swim in a parallel stream to mainstream British society. What makes Britain, say unlike America, an attractive country for immigrants, is that the concept of nationality or what constitutes ‘Britishness’ is fluid and less of a cookie cutter approach. True, there are still intrinsic economic and class barriers to integration but there is an appreciation and interest in what other cultures bring to the table. It is variety and cross fertilization of ideas and ways of being that makes a nation great and representative of contemporary society. Rishi Sunak typifies this new type of Britishness.

SC: ‘You lot have done all right in this country, haven’t you?’ observes the mother of Alice, PK’s son Amar’s friend. Indians in the UK, on average, earn higher than the national median income. The community is hugely successful occupying all sectors but predominantly in medicine, IT, finance and retail. PK is proud of his success, but it makes him individualist, as opposed to his friend Gupta, who feels his success is tied in with South Asian values. What’s your opinion on success and assimilation?

RR: ‘Success’ is such a loaded and subjective term and for immigrants like PK and Gupta, it is defined by tangible aspirational markers such as a detached house in a desirable neighborhood, a Mercedes and children being educated in a private school. As the Asian diaspora becomes more assimilated and comfortable and confident of their own identity, I think they will venture beyond this narrow, prescriptive set of parameters. This is particularly true of second or third generation British Asians, who might be drawn to the arts or following their own trajectory towards self-fulfillment in a way that’s not defined by what society or their community defines as ‘success’. Gupta’s son for instance is considered a ‘black sheep’ because he wants to be a poet in Paris. PK wants Amar to focus on math rather than art. In my own case, I was dissuaded from studying literature at university and was encouraged by my parents to apply for economics instead because of financial security.

SC: Your work is a departure from what has come to constitute ‘immigrant writing,’ a specific narrative which is palatable to the readership. In Still Lives, you centre the complexity of the character’s interiority, his desires and aspirations, rather than events brought about by the very act of immigrating. What are your thoughts on the narrow creative space, hyphenated identities are forced to inhabit, and is there hope the industry will allow us to explorer a wider range of issues?RR: Thank you for recognising this. Most novels with Asian themes follow the familiar trope of racism, poverty and discrimination. Mainstream publishers tacitly encourage works that play on the ‘exotic otherness’ and reinforces hackneyed perceptions of the British-South Asian experience. This makes it easy to categorize and label a novel. The danger in this kind of narrative is that immigrants are reduced to one-dimensional victims lacking agency or nuance. In Still Lives, I wanted to create characters who are multi layered with a rich inner life and dreams and desires that are not defined by their skin colour or ethnicity. As British-Asian writers we have a duty and a responsibility to create fiction that does not perpetuate stereotypes or is reductive of our culture. Writers are not one-trick ponies, nor are we ambassadors or representatives of our culture. Our aim is to explore the universality and commonality of human experience.

Selma Carvalho is a British-Asian writer whose work explores issues of migration, memory and belonging. Her debut novel Sisterhood of Swans (Speaking Tiger, 2021) was shortlisted for the Women Writers’ Prize (India) and listed among six notable fiction books of 2021 by Asian Review of Books. As a work-in-progress, it was shortlisted for the Mslexia Novella Prize. Her three non-fiction works document the Goan presence in colonial East Africa. Between 2011-2014, she headed the Oral Histories of British-Goans project funded by the HLF and archived at the British Library. Her short fiction and poetry have been widely published in journals and anthologies, among them by Kingston University Press and Parthian Books Wales. She has been listed or placed in numerous literary contests notably Fish, Bath, London Short Story, New Asian Writing, and winner of the Leicester Writes Prize. A collection of her short stories was a finalist for the SI Leeds Literary Prize and is forthcoming from Speaking Tiger in 2023. Her unpublished novel Horton was shortlisted for the Cinnamon Press Mentorship program. She lives in London.

Reshma Ruia is an award-winning author and poet. Her first novel was described in the Sunday Times as ‘a gem of straight-faced comedy’. She has published a poetry collection and a short story collection; her work has appeared in international anthologies and journals, and she has had work commissioned by the BBC. She is the co-founder of The Whole Kahani – a writers’ collective of British South Asian writers. Born in India and brought up in Rome, her writing explores the preoccupations of those who possess a multiple sense of belonging.

Still Lives published by Renard Press is out now.