Why should she feel as though she is living in somebody else’s house? It was hers by right. She had been the one to marry him and move with him to a house that resembled a hotel after all. The rooms do not feel as though they belong to her somehow, pale washes of blue and yellow wall intermittently admonishing her lack of acceptance. Admonishing her yet never changing. She knows she could have refused and stayed where she was but in the end she had agreed, believing it to be the right thing to do.

When her husband comes home late at night, she feels even less at home, uneasy even. More like their watchman back in Sylhet, the word sahib at the tip of her tongue, waiting to leave and greet him. But she knows that will be a mistake, too much like criticism to her stoical husband’s ears. He loathed frivolity. So she suppresses the wry smile and grudgingly allows herself to be wrapped up into the folds of sobriety, like an angora shawl, simultaneously comfortable yet annoying in its habitual shedding of lightest wool.

At dinner she hovers about the table until her husband finishes his meal, ineffectively warming a mug of lukewarm tea between her palms. She liked the feel of the ceramic coffee mug in her hands, tangible yet easily put down. She could have been watching the small black and white television in the corner of the room, but the thought of a solitary pair of eyes on them always made her feel lost. So to lose that feeling she would switch off the television she had been watching before he got home and go near him. If she stayed near him in this way she would always be alert, keeping an eye out in case he needed something.

‘Do you want more rice?’ she asks at the appropriate moments she has been taught to observe. The skilful nuances a good wife ought to know by ear.

‘No.’ He is always brief.

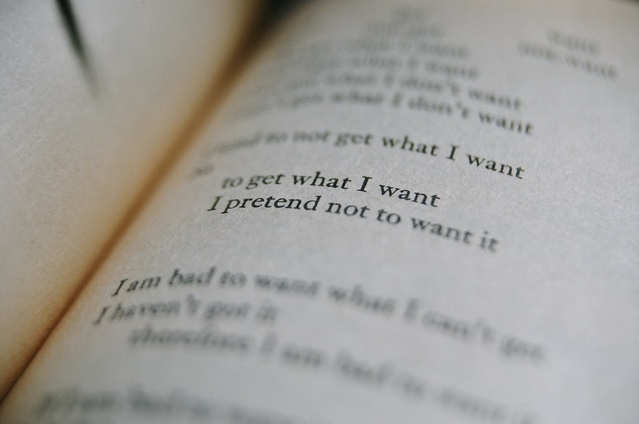

‘Be good at being a wife and you will give your husband no reason for complaint,’ her mother and aunts had told her repeatedly, the final time being at the departure gate at Dhaka International Airport. She wonders how she could learn this skill and be good at it. There were no signs that she could go by, no book she could read and follow.

He very rarely made eye contact, her husband. He would prefer to only speak if he needed to give her instructions or remind her of something that she needed to remember in future. It was always she who would need to remember things in future, never him. No, he does not want more rice he says when she picks up the rice bowl and offers to fill his empty plate.

The slow decline in his manners does not offend her as it once used to. She could live without his decorum. It was what most Bengali husbands did after all. She herself had grown accustomed to eating dinner alone. The habit of sharing food with a stranger held no appeal for her.

‘Make me some tea,’ he said, finishing his last morsel of rice and dhal. Although she has not touched alcohol in her life, she suddenly imagines the burning sensation of intoxication threading through her mind like some sort of wild music, rending reality haphazard and hazy. It was just his words. The way he made her feel so separated from everything. Always so abrupt. Was this apart of being a good husband?

‘You behave as though you’re a pariah in your own home,’ he tells her while she rinses the dishes, stirs tea. ‘Why don’t you do something to the place? Order new things; change the interior a little more to your liking?’ She gets the milk out of the fridge and pours it into his tea, adds two spoons of sugar. ‘This place could do with a woman’s touch.’ He stops and sighs, exasperation making him appear unusually angry, though she knew he was not angry at all. It was the fact that she had broken his bachelor’s routine by arriving here. She too stops, waiting for him to leave. She wasn’t dead, so why was he speaking as though she were a corpse? ‘It’s not enough to just live,’ he says as though reading her mind. Shame touches her briefly, lingers over her skin in pinpricks soft as a breeze, and then releases her.

And it is only after she hands him the tea and he is gone that she resumes wiping the counters down, drying dish after dish. Finally, after a few moments she finds herself lost in the floral prints of the crockery, imaging fields of yellow mustard and shapla flowers floating dreamily in the water by her parents’ house. She did not like him to interrupt her work, his intrusive eyes making talk she had no need for.

‘What’s the point talking to you? You don’t even listen.’ It was the voice of a husband who had stopped talking to and had begun talking at his wife.

But she had listened. How did he know she was not? Her silence did not diminish her ability to hear him. She felt like asking if in addition to the many letters after his name the ability to read minds was also listed. Perhaps he could teach psychic phenomena at the university instead of science? She could imagine him, waving his arms about fluidly, making himself appear larger than life, as he was a tall man of six foot two, a tall Bengali, opening and closing his mouth as he spoke. His students no doubt watching that mouth, wondering when the lecture would end and they could go home, away from this mad professor.

‘I don’t know why you can’t accept this country as your home; forget the country, just this house would do. I didn’t know you were so against moving…why didn’t you tell me? Why didn’t any of your family tell me?’ She heard him pacing, his Bata slippers grazing the wooden floor, giving another lecture in the small theatre of his home, making her feel like a burden.

He had never asked her. No one had asked her how against moving she had been. Had she been a fool thinking they would just be able to see it in her eyes? Had she over-estimated the people she had loved all her life? Should they not have seen how she hurt for them, how she had wanted so much for them to be happy that she was willing to remove herself from the folds of their shelter and love? No-she had been stupid. They had the ability to see that as much as her husband saw her now. It was just letters after names and the pull of duty in the end, nothing more.

Her husband continues talking. A monologue she knew off by heart. Her ears go back a day, a week a month. ‘Don’t I make you happy?’ he is saying. But she does not want to hear about happiness. His kind of happiness. What was happiness after all but a sheet of music read and easily forgotten? When he talked like this she found herself slowly being buried into those words he liked to use all the time in order to make her feel guilty. Love and Happiness. I want a life of my own. She wants to tell him she values this more. She wants to but she hesitates. She was his wife and being his wife was what had brought her here. ‘Aren’t you happy with me?’ he would ask her. She could not bring herself to answer him.

Most weekends they entertain his friends. Three single men in their late twenties, who had not yet had a chance to go ‘back home’ and select a suitable wife. She could imagine what that would invariably lead to…recipes for kurma and shondesh and tips on how to perfect a knitting pattern and the most economical way to manage housekeeping money their husbands had collectively gone out and earned. She would attend parties for everything ranging from a baby’s rice ceremony to the mango and jackfruit season dinner party. Bengali’s loved a party and food. Any occasion was revered as auspicious, therefore requiring a party. And this socialising would amass to never-ending small talk and sari wearing that would eventually drive her insane.

All of this she dreaded. She did not want to keep up appearances and smile, she wanted to laugh and joke and feel the real warmth of people who knew and loved her, not sit amidst the pack of newly arrived brides, zealously recounting their gold jewellery and Benarsi silks. And all this talk of babies, and pregnancy? Was that all her life could amount to?

Soon, before the year is out, there is an influx of South Asians in the neighbourhood, and the new wives begin pouring in, wide-eyed and apprehensive. Anticipating palaces and receiving a run-down bed sit somewhere off the north circular. In this respect she ought to have been happy. At least they lived on the grounds of the university where her husband taught, in a nice little house, not grand yet comfortable. Her parents had chosen well. A good provider. She ought to have been happy but she wasn’t. It was just walls and a heavy wooden door that closed in on her heart, choking her with the intense pressure of its foreignness.

On their first day she had followed her husband through the door, eyes struck by the lack of sunshine, sandaled feet resting barely beyond the threshold, so tentative. The house was stale in its inability to evoke any form of emotion from her. She had stopped. The tiny bag he had allowed her to carry from the airport had slipped from her shoulder and fallen onto the floor, sharply bringing her to attention. She had arrived. And as she peered inside she was shocked to discover that it was only walls that greeted her, pared down, colourless and indiscriminate in their coldness towards her. Like a family that no longer wanted to carry the disgrace of its’ offspring.

‘God willing you will be happy here,’ her husband had smiled, allowing himself a brief moment of tenderness towards his new bride. A hand on her shoulder, a kiss on her forehead, as though he was blessing her. She remembered that one kiss as it settled into the stilled air of hindsight, tugging at her conscience every now and then. There had been such awkwardness within the intimacy. The magnitude of that awkwardness had stunned her and she had not responded, choosing instead to stare fixedly at the walls, pale and barren. Sighing as the end to their wait for occupants had arrived. She had felt tears then, the tears of a fool. And nothing but contempt for this man that had forced her to cross oceans only to be greeted by bare walls with not a single picture or a friendly face in sight. And it was then that she had realised that he would only be happy there.

At night, as usual she feels as though the house is observing her, the glass paned windows stealing her reflections, snatches of a slim woman in a cotton sari, all braided hair and new bride glitter plotting to hush them, hush them. It had been said that if a woman looked into a mirror at night it soon devoured her soul. An old Bengali fable that she disbelieved yet accepted as she stared and stared at her reflection, wishing she could disappear into the mirror.

‘Didi?’ Shobna brings her back from her reverie.

‘Didi! Look! Don’t you just love this cross-stitch?’

‘Cross-stitch?’ she whispers, barely audible. She had forgotten that she was stitching.

‘Didi are you alright?’

She feels then that Shobna is mocking her as she repeatedly calls her didi. Shobna was at least five years older and for her to call her older sister made her feel incompetent. Had she aged so much in such a short time? Perhaps Shobna deemed her a happy expatriate only too willing to explain London to a new arrival. She stared at Shobna and wondered if she knew that she was asking the wrong person. Aamir had been the first of the three bachelors to bring over a wife and Shobna was her first attempt at trying to befriend a stranger.

‘Yes I’m alright Shobna,’ She smiles. ‘That is really a nice cross-stitch.’ And so the friendship of craftswomanship and sari choosing began in earnest.

Shobna and Aamir inevitably become friends that visit them on weekends and they hold dinner parties in each other’s houses, inviting their ever-increasing circle of Bengali friends. And then one summer Shobna announces that she is to have a baby. And it is not too long after that she herself has a baby, joining the exclusivity of the truly married club with children. They reluctantly become confidantes if not friends, talking about the pains and pleasures of child-rearing and the indifferent attitudes of their husbands who only wish to hold the children for a minute or two when they are freshly bathed and sated with food.

As the years pass they take the children, a little boy and a little girl for a stroll in the park then when they are old enough they put their names down for admittance at the same nursery feeling and seemingly proud, though you never could tell just by looking at the faces of the two women if it was Shobna or herself that was dying inside.

From time to time she allows herself to look back to a place where she had wanted her own life separate from that of domesticity but that image leaves her more quickly these days like a blinking eye in a sandstorm. And in an instant she becomes an extension of her husband who still wonders if he makes her happy as she smiles at him.

Dina Begum is an East London based writer and poet currently working on her first novel Six Yards of River as well as writing short stories for Creative Week Newspaper.