On arriving at HeHo, the nearest airport to Inle, we were met by Major who took us straight to their pier and our boat for the journey to the monastery. A sense of calm befell me. I felt I was back where I belonged. The hustle and bustle of Yangon and the trials and tribulations felt a long way off. I was wrong, of course. But right now I was happy to be back within striking distance of the monastery and the children. We were greeted by our usual boatman. It was very quiet. The monsoon meant there were few tourists. The sky was cloudy and you could see localised bursts of rain from patches of dark clouds in the sky…a sure sign that we were witnessing the beginnings of the monsoon season. Although there was the occasional drop of rain, we kept dry. Major quickly drifted off to sleep. I imagined he was used to snatching sleep wherever and whenever he could during his cattle smuggling days.

When we reached the hotel at Inle, we were welcomed in the usual way by a somewhat spartan kitchen band. I spotted cousin Ting and Bo Kyaw both beaming away on the jetty. Ting rushed towards me and gave me a big hug and congratulated me on the publication of the book. It was something we had inevitably discussed on every trip and finally it had happened!

After a quick wash, we met up in the hotel restaurant, which, like the hotel at this time of year, was virtually empty. I handed over copies of my book wrapped, naturally, in saffron paper. They proceeded to undo them slowly taking great care not to damage the wrapping paper. The waiter offered a pair of scissors but these were declined. Finally all was revealed and they seemed more than happy. There were lots of hugs and I cracked open a bottle of the duty-free whisky I always bring from Heathrow.

Over dinner, Ting brought up the subject of the increasing tension between Muslims and Buddhists. He also suggested that publishing the book in Myanmar might help draw attention to a positive relationship involving both faiths which was happening right there on the ground. He would arrange for me to meet the publisher in Yangon who was working on the memoirs of his late father-in-law.

After all that excitement, we turned to the main purpose of our trip – the water project. We were going to need a list!

- 1. Contact Kyi Kyi Mar’s office to check on the progress of the machinery which was due to be taken by road to Nyaung Shwe where Phongyi’s man would be waiting to load it onto a boat for the six hour journey to the monastery.

- 2. Check with our PNO man in Yangon, Khun Maung Saung, on the progress of the design and production of the wrapper and bottle tops.

- 3. Check up on the money situation! We would need to go through the books (which were in part kept at the hotel) to check the costs and to see how much more we were going to need to complete the project. Actually, this really ought to have been the priority but I didn’t want to let the small matter of money distract me from a sense that we were getting there. And in any case, much better to be able to see some physical evidence of the progress we were making.

- 4. Contact Phongyi at the monastery to see if the engineer could increase the flow and force of the water. Since Ting, our guiding hand on the project, would only have one day at Phaya Taung, this would make planning and designing the structure easier and also allow him to more accurately estimate the calibre of the pump and compressor needed and judge the size of the water storage tanks.

All the whisky, green tea and excitement made sleep impossible that night so I lay awake going over and over the details. Thankfully, the next day was a rest day so we went out in the boat shopping. I wanted to get one of the lotus scarves we had seen on an earlier trip as a birthday present for my publisher, Chris Day.

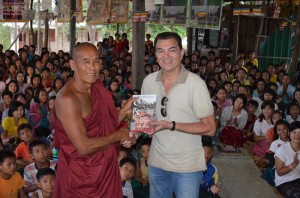

We left for the monastery very early the following morning because Ting had to be back that evening and so I wanted to make the most of his time. On arrival, we were greeted by at least 100 students who were all lined up at the jetty – quite a sight and a much appreciated gesture – as was usual.

We walked up the hill and I could hardly believe what I saw: an immaculate new building glistening in yellow and green. Peering through the open doorway, I noticed the sparkling tiled floor. This was the new Ko Yin Mineral Water factory, finished. I was in awe! Phongyi had made sure it would be a surprise and it certainly was. He was always ahead of the game and had delivered way ahead of my expectations. This was an incredibly happy moment and the best possible present I could have received, but I also knew we had a long way to go before we would start seeing Ko Yin water bottles pouring off the production line. The end was in sight but there would be some uncomfortable bumps and tight turns to negotiate along the way.

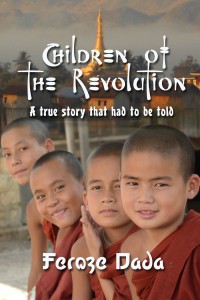

Feroze Dada was born in Karachi. He has lived and worked for most of his life in London. He is a qualified chartered accountant and chartered tax advisor. This is his first book, but hopefully not his last. Feroze travelled with MuMu (Farida) Dada – photographer, interpreter and guide. MuMu was born in Taunggyi, Burma and then lived in Karachi. She currently runs the family’s property business in London. MuMu and Feroze met in London and were married in Pakistan. They have two grown up children, Sumaya and Nadir, and divide their time between their homes in London and Italy.

This is an extract from Children of the Revolution, by Feroze Dada published by Filament and available in hardback and ebook.