by Jacqui Lofthouse

There are many stages of the editing process – which may be one reason why many writers find editing a confusing and occasionally frustrating process. So often, we enjoy the first rush of enthusiasm that seizes us when we begin writing a book, but it is more difficult to keep that verve alive when we have to take our words to the next stage. We are obliged to return to material that spilled from our right brain almost effortlessly and engage that more rational left brain if we’re to make those words into something more readable, more polished and more perfect.

Yet editing is an essential component of the writing process and if we can learn to enjoy it – indeed to relish this work – then our writing will benefit hugely. I am currently working on the third draft of my fourth novel and thus am no stranger to the editing process. Once a week I take myself off to the British Library for a long day in the Reading Room and devote myself to this fiddling with words: taking out those which no longer suffice; adding a little additional dialogue here; polishing a metaphor; or writing a new scene to deepen the reader’s understanding of a character.

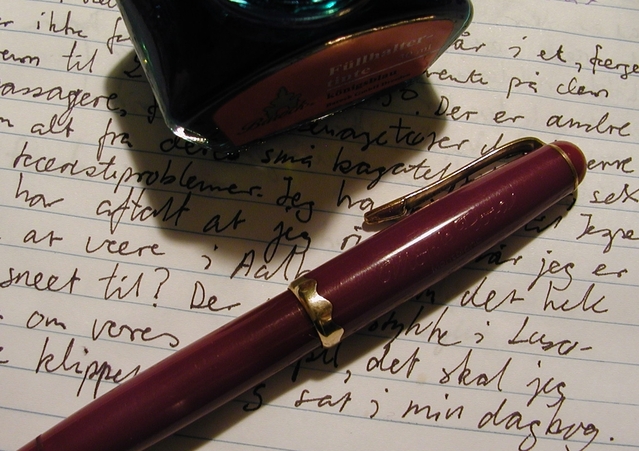

For me, the process of writing would be incomplete without editing. Indeed, editing is part of my regular writing ritual. Each night, on writing days, I print up my latest work and read it, curled up in the armchair, pencil-in-hand. I pencil-annotate that document, as if I were a publisher duty-bound to improve it, as if that prose had not been written by me. There’s something about seeing the manuscript in printed form that distances me from what I have written – and it makes the errors glaringly obvious. If I’m using six words when one will do, it leaps out at me. Indeed, I’m always cutting words out with that pencil, paring down my prose. Avoiding excess words is one of my principal rules. I learnt that particular one when I delivered my novel ‘Bluethroat Morning’ to my agent at 180,000 words. She read it through and returned it to me. ‘Very strong,’ she said. ‘But you need to cut 40,000 words’. Astonishingly (and I still barely believe this one), this was something I managed to do, without altering the storyline one jot. I did it line by line, cut out 40,000 words just by pruning. The story remained exactly the same. Every scene was intact. What remained was a narrative that was more elegant and also more pacey. At a later stage, once I’d sold that book, my editor at the publishing house asked me to add some plot developments. In that rewrite, I added 20,000 words back in, but they were 20,000 essential words that added to characterization, the backstory and the central storyline.

Each day, when I begin writing, I take the pencil-annotated document from the previous evening and I make the changes onscreen, before moving forward with my new writing for the day. Sometimes, when I haven’t done the pencil-editing, I simply skim back a page or two and do it by hunch, there and then, direct to the screen, before moving forwards. It’s a kind of warm-up and gets me back into the story, I find my flow again.

This is what I call a line-by-line edit. It’s not looking at whether a character is working or whether I’m getting the plot right. That’s ‘big picture’ editing and comes later. But this daily perfecting of my work helps me to be freer in the writing itself. Because if I know I’ll be editing regularly, then I also know it’s ok to write badly. It’s ok to get into the flow and not worry about the detail. Tomorrow I’ll be putting it right after all.

What I’m looking for, in these line-by-line edits, is to cut out the fat, the unnecessary words that hold up the storyline, that have no meaning, the words that are simply padding – they get in the way of the essence of my story. I’ll also look for weak or unrealistic dialogue; for dull prose; for cliché and lazy writing; for words that are simply unnecessary. Sometimes a whole paragraph will go. Generally, if I’m working well, then what I’m left with is prose that is tight and clean; I get a sense that I’m not wasting words. I value words too much to throw them away. And when my writing is as elegant as I can make it, then I know I can move forwards. My plot might not yet be perfect. (The first time I wrote that, I wrote – my plot might not be perfect yet, but I prefer it the other way around.) I might feel that I don’t yet fully understand these characters. But my prose has a good flow and that gives me a certain confidence. The bigger stuff can come later, but for now I have a work which will keep the reader involved, and hopefully leave the reader wanting more.

Something else I’m looking for when I’m editing fiction is pace. Am I wasting time telling the reader how a character gets from A to B? Surely a jump cut will work better? Am I showing off my knowledge, when really the reader doesn’t care two hoots? Again, it must be a case of: ‘slaughter your darlings’. There are times when there’s a good reason for digression, but if one does digress, one must always be sure of one’s purpose. A digression must not be mindless. Equally, I always tell my clients to write each scene with a sense of direction. I’ll ask: “What is moving forwards in this scene?” or “ How is it progressing the plot and the character development?” If a scene does neither – assuming you’re not writing more experimental fiction – you might be in trouble.

The next stage of editing is editing that happens in the process of writing. It’s the continual adjustments that we make in our mind as we work. It’s what happens when we mull over a problem about the book in our heads, unable to find an answer – yet we discover that answer later, suddenly and quite unexpectedly when we’re out walking in the park. When we’re in flow, there’s a mental editing that goes on all the time. We can’t stop thinking about the work. We’re asking ourselves how to resolve a particular plot issue or how an action taken by a character could make sense. When the answer comes, it’s important to jot it down (you do always carry a notebook, don’t you?) Then, when we return to the work, we can jump in and make an immediate adjustment, write a scene that redresses the omission or the previous confusion.

If you’re looking for more inspiration around the writing process, why not check out ‘The Writing Coach’ eBook, which condenses my experience of the writing process into simple 30 day programme: http://www.thewritingcoach.co.uk/bookshop.php