by CG Menon

It isn’t until she gets to the bus stop that Malathy knows her feet are wrong. They’re aching a little and bulging from their lace-up shoes under the hem of her sari, but that’s not it. Perhaps they’re just tired; she’s already trotted along miles of vinyl corridors behind the hospital tea trolley and clumped through the evening’s drizzling rain. She sits down, shakes her legs, and reads the graffiti daubed on the concrete wall. Alex Loves Sara. She likes that, hopes he does, but perhaps Sara wrote it herself. It’s been that sort of day.

She frowns at her feet again. They’re throbbing and damp and somehow she thinks they shouldn’t be here at all. They should be fins instead; green and scaled and shimmering, with a shiver of muscle running down to the tip. It’s an old trick from her childhood, when she used to sit on the damp concrete outside the Marina swimming pool in Madras and pretend to be a makora. A sea monster. She used to go further, pretend she had the swirling peacock feathers, the doomed and tragic eyes. Not anymore though; not here.

But now it appears she’s a makora again, and she examines those sturdy ankles that swelled when Rahul was born and haven’t really gone down since. She hadn’t thought that sea monsters had feet, but perhaps it doesn’t matter in the end, and so she picks up her shopping and climbs onto the waiting bus. In the distance the Tyne swirls in an eddy of turbid brown.

She remembers another river, diamond-bright as it bubbled over her toes. A stream, really, with a bed of stones polished to smooth curves. She remembers the hillside near

Middlesbrough, sloping and littered with greyish flints, and the distant factory chimneys that puffed out clouds of pure white smoke. Sheep-white and grass-green and sky-blue, she remembers, and the sun beating down forever on the clover that stained her hands.

She shifts her grip on the string handles. She’s got cod for Bill’s dinner, and she thinks she could stretch it for two days with some dal. Bill’s not too fond of dal though – calls it fancy foreign muck when he’s down at the pub, but he’s gentle too; tries to make sure she doesn’t hear.

They’d had dal that day too, dolloped into lukewarm plastic containers, and squashed with the chapattis into her mother’s leather bag. That bag had come across with them all from Madras only the winter before – Amma and Appa, little Anil, Malathy, Durga-chechi with her woollen cardigans. All of them left a bit battered; all of them frozen and brown in a grey-white city.

And on their very first family outing – and this was the point in the story where Amma’s eyes widened and her voice dropped with a delicious swoop – Malathy had got lost, somewhere on that steep green hillside. It’s part of the family folklore, like when Blackie ran away or when Anil was summonsed for cycling without a light.

“When we called to fetch her back, she was gone!”

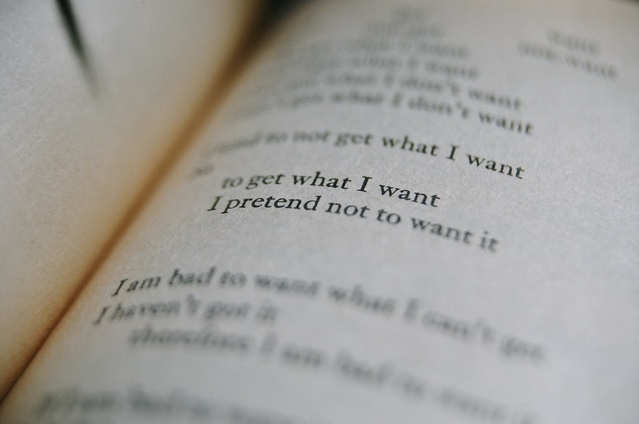

The suspense doesn’t last long, they’d found her half an hour later playing with flints and in a tantrum about being taken back home. But Malathy knows there’s another part to it, a part broken off like a jagged tooth in the back of her mouth. In that part, she wades upstream to a rocky crevice covered in fairy-green moss. Hidden deep within the spongy softness she uncovers a cleft where the water springs fresh and bubbling, finds a cavern just behind it that teems with nymphs and sirens with fish’s tails. She dives in through the stony lips, she’s tossed by waves and ground against rocks until she emerges polished as flint and changed into something else entirely.

#

Bill’s waiting at home when she arrives, sitting in his old brown armchair by the television. She keeps meaning to have the place redecorated, but you can’t get that sort of flock paper nowadays, and plain paint reminds her of slums.

“It’s fish tonight, dear.”

She struggles out of her coat, the solid shape of her hips and shoulders stretched into the cloth, and runs cold water over the greasy breakfast dishes. Bill will leave his plate on the table, egg drying out and toast crumbs down the front of his shirt. He’s kind, though; she gives him his due even inside her head as the gas fire starts to warm the chilly kitchen and the fish splutters in the frying pan.

She shuffles back through to the living room, where Bill’s chisel and hook knife lie on the table next to a half-carved toy horse. Something for Katie, Rahul’s first and such a pretty fair girl, but she’s getting far too old for wooden toys. She hopes Bill won’t mind. Since he retired from the carpentering he likes to keep his hand in with carving, but it’s all Lego and Sindy dolls now, and to tell the truth he never really was that good. He was a practical carpenter, turning out solid objects that lasted. She’s glad he’s stopped, she thinks, stretching her toes inside her worn carpet slippers. There are already too many things in this country that last.

“I can’t even swim,” she says abruptly.

“Eh? What’s that, pet?” Bill leans forward and switches off the set, looking at her with puzzlement. She can smell the fish smoking away in the kitchen – it’ll be burnt, but he’ll chew through it manfully and never notice.

“I want to learn how to swim.”

He eyes her warily, and she can see he’s wondering if this is the change. She’s too old for that though; went through it ten years ago and had the house turned upside down with her sweats like the monsoon.

“They have those aquarobics classes,” he ventures. “Down at the baths.” His eyes are bleared but he’s trying to please her, and so she sniffles a few times and hurries back to the kitchen to sit with her sari pulled over her head and listen to the dinner burning.

#

It’s raining the next day, a cold drizzle, and her fingers are numb as she moves about the kitchen straightening things up. It’s her day off, and someone else will have to dole out the polystyrene cups of scalding tea, and feel the edge of Annie Higgs’ tongue. Annie’s got cancer, lies drenched with pain on a crumpled pillow and calls her a Paki when it gets too bad, though Malathy’s never been near Pakistan in her life. She says she’s just waiting to die, but Malathy knows differently. She’ll hang on a good few more years, long past the time when Malathy herself will slough her skin and swim off instead with a monster’s tail polished bright as an iron lung.

Bill’s in front of the television again, puffing out yellow fug from his pipe. She’s been asking him to stop for years, but he likes the feel of the stem in his mouth and anyway he spends more time fiddling with it than smoking. She used to mind the circle of dusty grey around his armchair where the ash grinds into the carpet, but by now she’s used to it. Occasionally she imagines coming back home one day by herself, turning the stiff key in the

door, wearing her white sari for the first time since her wedding – Bill’s Mam insisted, said it was the proper colour for brides, and Malathy had practically grown up here anyway, it wasn’t as though she was really foreign – and seeing that island of ash.

“I found you those swimming classes,” Bill announces. He’s been up since five, he doesn’t sleep much anyway and he’s pleased to have a reason to be up out of the roil and muddle of the tangled bed sheets. She frowns. She knows what she said last night, and it’s true – she thought she was a makora, and it’s not as though you can be changing much at her time of life, so she supposes that she still is – but she no longer thinks that swimming will get her anywhere.

“Three o’clock.” He hands her a brochure that must have been sitting in the back of a drawer for months, along with a takeaway menu and a notice about council meetings. “Senior Citizens Aquarobics”, it reads. It’s bright and glossy, with a picture of some smiling, shining nymphs; senior citizens in bright pink bathing caps. They’re poised on the side of an ominously blue pool. Don’t jump, she thinks; thinks of lemmings and suicide pacts and village girls flinging themselves from mango trees with rope around their necks. “Classes at 3pm”.

She examines the picture dubiously. Perhaps somewhere in that chemical blue there’s a rent, a gap where she can slip through to the palm trees and storm-filled skies of Madras, but she doesn’t think so. All those ladies look too solid for that. They look like they’re built to last.

Nevertheless, she agrees to go and have a look. Do some shopping, have some tea in town before she comes back to make the jam roly-poly for tonight. Bill would like her out of the house for a while, she knows. His sports programme is on soon and she’s been edgy, snapping at him and burning the fish last night, although he’d never dream of saying so.

She takes a small rucksack with her; one of Durga-chechi’s old cardigans and a book for the trip. The pamphlet Bill gave her has the route to the baths, but she doesn’t need it. She’s not going to town, to aquarobics and shopping and tea. She’s going back to find those stones that cut like glass and that spring that bubbled out of the fresh-tasting earth. She’s going to scatter everything to glory with a single flick of her peacock tail; breakfast plates and bathing caps and bunions and all. She’s going back to Middlesbrough.

She thanks the bus driver as she clambers down at the station to catch the express. He’s a young lad, with a shock of hair like Anil before he went into the navy and cut it short and got himself killed in that accident out in Australia. She pulls herself together; the afternoon is too bright, too chilly with sharp gusts of wind and anaemic early daffodils, to start to remember that.

“Middlesbrough” says the board on the next bay, and so she climbs onto the express bus and tugs her blouse down against the cold. She has no picnic this time; no dal in plastic containers, no cold chapattis to stick to her fingers, nothing but a cardigan and a cheap rucksack, and it worries her. This is a journey. She should have taken provisions.

A few more people shuffle on to the bus. It’s half-past two on a bright Tuesday afternoon, and that’s a definite time, a time for appointments and grocery shopping and bank managers. It’s a time to be jotted in a diary with a ballpoint pen, but these grey-and-white people don’t seem to have any plans at all. She rummages in her rucksack as the bus rolls out and finds a barley-sugar. She unwraps it and then, sucking, drops the paper deliberately on the floor. It’s her own form of graffiti, Malathy was here, and she wishes she’d thought of it earlier.

#

She dozes, and wakes to find that they’re trundling along a valley floor just outside Middlesbrough. It’s dark now, and hills rise on either side with their tops still lit by the flattened rays of sunset. The sloping ground is littered with flints and criss-crossed by wavering dry-stone walls, and there’s a cairn on the highest hillside. It’s a tottering pile of rocks that catches the sun with a reddish glow and sends a shadow stretching like a finger towards the road. She rings the bell hurriedly and hopes the bus stop is nearby.

She’d thought she would recognise somewhere, remember something, but the bus has come to a juddering halt, and there’s nothing left to do but climb down and stand under the fluorescent tube of the bus shelter. She’s stiff now – too many hours on that seat – and her jauntiness has ebbed away to leave a strange, spreading misery. She’s small again, she thinks, she’s frozen and brown, she’s fancy foreign muck.

The hillside rises gently, close-cropped grass scattered with rabbit droppings just becoming visible in the pallid moonlight. There’s a remembered taste in that rising wind, the Royapuram harbour after a storm. It’s an old taste, a salt-and-decay taste of storms and weed and ocean slime, and murky waters covering things best left forgotten. Cars roar past on the road below. She’s high enough that their lights only catch the edge of her coat, and she thinks with pleasure that she must resemble something quite natural – a rock, a tree – and not Malathy at all.

She reaches the cairn, still warm from the sun. Round the leeward side it’s windless and calm, and she lowers herself down against the stones. The air here is quiet, and the grass has grown rank in long, weed-like strands that break under her fingers. The rocks against her back are colder than she’d thought, and feel less secure. Like the drystone walls – like a lot of things built to last – there’s nothing holding them together.

Just over that rise, she thinks, there could be a little rocky gully with a bubbling stream and a crushed smell of clover and that miasma that rises from the grass at night. She could walk to the very edge of the cairn’s long shadow and tug off her shoes, barefoot in the warm dust in the way she remembers. She could wade along the river, past the sharp-edged stones, and the silvery tadpoles and the splash and gurgle of great eels, past the bow waves of gigantic fish, past the worms hundreds of metres long and the flattened serpents that churn and coil in the current. She could be swept off her feet by the tidal surge, swept over a bottomless chasm of water the exact colour of her monster’s tail.

She pulls her sari straight and settles back further in the grass. Before she thinks about any of that, though, she has some things to leave. She doesn’t expect to miss them, but just for a second she feels strange. Like a lemming, she remembers thinking a long time ago. Like a suicide pact. Like a village girl in a mango tree.

And so she leaves a sea monster here, under the stones where she can hide until her skin gleams new as copper. She leaves a bride, dressed in red and gold and all the colours of the sun. She leaves Annie, who’s never seen a hospital trolley in her life; and Alex, who loves Sara and always will; and Anil, who came back from the navy and wrote them every single day.

#

It must be an hour later by the time Malathy stands up. The wind has risen, and she begins to feel her way through the flints to the bus shelter below. Bill will be wanting his dinner, she thinks, and starts to count ingredients in her head. One egg, two eggs. Suet for the jam roly-poly.

C. G. Menon has been published in a number of venues and shortlisted for several awards including the Willesden Herald competition, the Fiction Desk Newcomer prize, the Tower Hamlets WriteIdea competition and the Words and Women competition. She lives in London, and is currently working on her first novel.