AA Dhand

When Ali met Honour is a refreshing look into a seldom explored genre and brilliantly written by two debuts authors. Ali is a British Asian who is involved with Honour, a middle-class English girl. The co-writers, Dimmi Khan and Antsey Spraggan write from the points of view of Ali and Honour respectfully. The book takes us across Manchester, London and Kent exploring many cross-cultural issues, always tactfully and always uniquely. The book’s strength is subverting common clichés and whilst there are elements of stereotypes, Ali and Honour’s love-story brings out the best of both their worlds. It is an emotional rollercoaster – the reader never able to guess whether we will have a happy or tragic ending. Honour is a fabulous character – her love for Ali is clear, yet she continues to put the reader on edge by allowing her fiery temper to take her relationship to the brink. At times, the story was so compelling I had to put it aside, take a break and remind myself that it was fiction. Great characters, great story – great drama. The ending was beautifully done and the sign of a great book is, after reading “The End”, the tale stays with you.

Roopa Farooki

My book of the year is a quietly arresting book on loss and resilience, on personal journeys made and what they cost us, and how they might ultimately reward and even redeem us. In Spite of Oceans, Migrant Voices, by Huma Qureshi, is one of those books that doesn’t make a lot of noise, but which shines a bright light into hidden corners; the stories ring with a resonance that remains with you after louder and showier narratives have faded. The prose crosses borders into fiction, and I was reminded of the luminous and insightful interviews from Theodore Zeldin’s An Intimate History of Humanity. Qureshi’s gift is that it doesn’t feel that these are other peoples’ stories, or private memoir, but that they belong to all of us. It leaves us with bittersweet promise, which I hope will be fulfilled in her next book.

Niven Govinden

Having previously tweeted my books of the year (#nivsbooks2015), I’m using this wonderful opportunity to mention further books of equal obsession. Firstly, Andrew McMillan’s Physical (Jonathan Cape); poems whose boldness and fragility marked different readings, but were never anything less than honest, and always beautiful. Am so looking forward to what he writes next. Max Porter’s Grief Is The Thing With Feathers (Faber) blew me away with its dark playfulness and grace. Again, from the opening page, I knew that this is a writer that I will always want to read. Per Olov Enquists’s The Wandering Pine, translated by Deborah Bragan-Turner (MacLehose), a stunning autobiographical novel on a writer’s beginnings. Long after finishing, it’s a book that continues to resonate deeply. Finally, The Vegetarian from Han Kang, translated by Deborah Smith (Granta). Next level fiction: thrilling, disturbing, and meaty.

Romesh Gunsekera

This year I have rediscovered Frederico Garcia Lorca and Jose Rizal. Lorca is the iconic poet of Spain who was murdered in 1936. Rereading his Selected Poems has reminded me of how powerful a short lyric line could be. In his poems one returns to images of the moon, the sea and the rider and narratives of death and difficult love which are intense and brilliant. Rizal also wrote in Spanish. He generally regarded as the father of Filipino literature. His novel Noli me Tangere, written in the 1880s, is surprisingly modern, humorous and explosive. A surprising treat.

Vaseem Khan

A truly great book leaves an emotional imprint that lasts for years. That’s why they are so rare. This year I came across two such novels. Richard Flanagan’s The Narrow Road to the Deep North, a previous Booker winner, is an authentic evocation of the suffering of Australian POWs in the jungles of Asia; a study of a deeply flawed character who nevertheless displays heroism (even though he would not label it as such), and an understated romance all written with brilliant lyricism and bleak, near poetical prose. I cannot recommend highly enough. My second great book, surprisingly, is a teen romance – not my usual territory, but the hype around John Green’s The Fault in our Stars is well deserved. This novel is about terminal illness, yet managed to make me laugh out loud so many times I lost count. Hazel and Augustus are teenagers with cancer, but their love story unfolds with such a passion for life that we are completely sold. The author has perfectly captured teen angst, teen humour, and adolescent love. At the same time this book transcends its genre with genuine musings on how we define life, what its purpose is, and how best we can do justice to living it. Simply brilliant. Be prepared to laugh and cry.

Adrienne Loftus Parkins, The Asian Reader

Although this has been an exciting year for books about Asia, I decided early on that this would be my year to catch up on some non-Asian reading. I jumped on the Neapolitan bandwagon after a friend said absolutely must read My Brilliant Friend by Elena Ferrante. I struggled through the first half wondering why everyone seemed so taken with Ferrante’s quartet about two friends growing up in the slums of Naples. But by the end of the first book I was totally hooked; I had to read the others back to back. Finishing the fourth and final one, The Story of The Lost Child (published in September), left me bereft that there would be no more of Elena, Lila and their personal struggles, framed against the violence and changing mores of mid century Italy. Back to Asia with Amitav Ghosh’s finale to his Ibis trilogy, Flood of Fire, a gripping and entertaining read that brought to a rousing finish the tales of the opium trade that he began in Sea of Poppies and continued in River of Smoke. Ghosh is a magician whose talent with language, commitment to facts and ability to flip between history and humour enabled him to keep his readers engrossed throughout three very large volumes. Finally, a few words about Anuradha Roy’s Sleeping on Jupiter. This is not a book I highlight because it shares the entertaining qualities of my previous choices, but because it signals a departure from the stereotypes that can often characterise fiction from the subcontinent. Here Roy says what has previously been almost unsayable about violence towards women. It feels like a sea change in what we expect from South Asian literature – a topical story reimagined, a hard message, beautifully written.

Bina Shah

My reading was more sparse than usual because I was working on a novel this year, but I managed to squeeze in a few good reads. The Upstairs Wife by Rafia Zakaria, about her aunt’s travails as a first, “upstairs” wife living with the second wife downstairs in the same house, and a husband who moves back and forth between the two self-contained units. Set against the backdrop of Partition, then Pakistan’s early history, the book intrigued me with its twinned threads of personal and political history. H is for Hawk by Helen Macdonald which is raw and unflinching in its treatment of grief and bereavement. When a daughter loses her father suddenly and unexpectedly, the only thing that can heal her wounded heart is the female goshawk, Mabel, who tames and is tamed in equal measure. Poetry and prose, gorgeous language. An Unnecessary Woman by Rabih Alameddine. Aaliya is a 72 year old woman who lives on her own in an apartment in Beirut, surrounded by boxes full of the books – classics and obscure novels – that she’s spent her life translating but never had published. Eccentric and reclusive – she dyes her hair blue by accident in the opening pages of the novel – her inner life is rich with literature, art and music. As much an ode to literature as to the city of Beirut, this is a rich and captivating read.

Jemimah Steinfeld

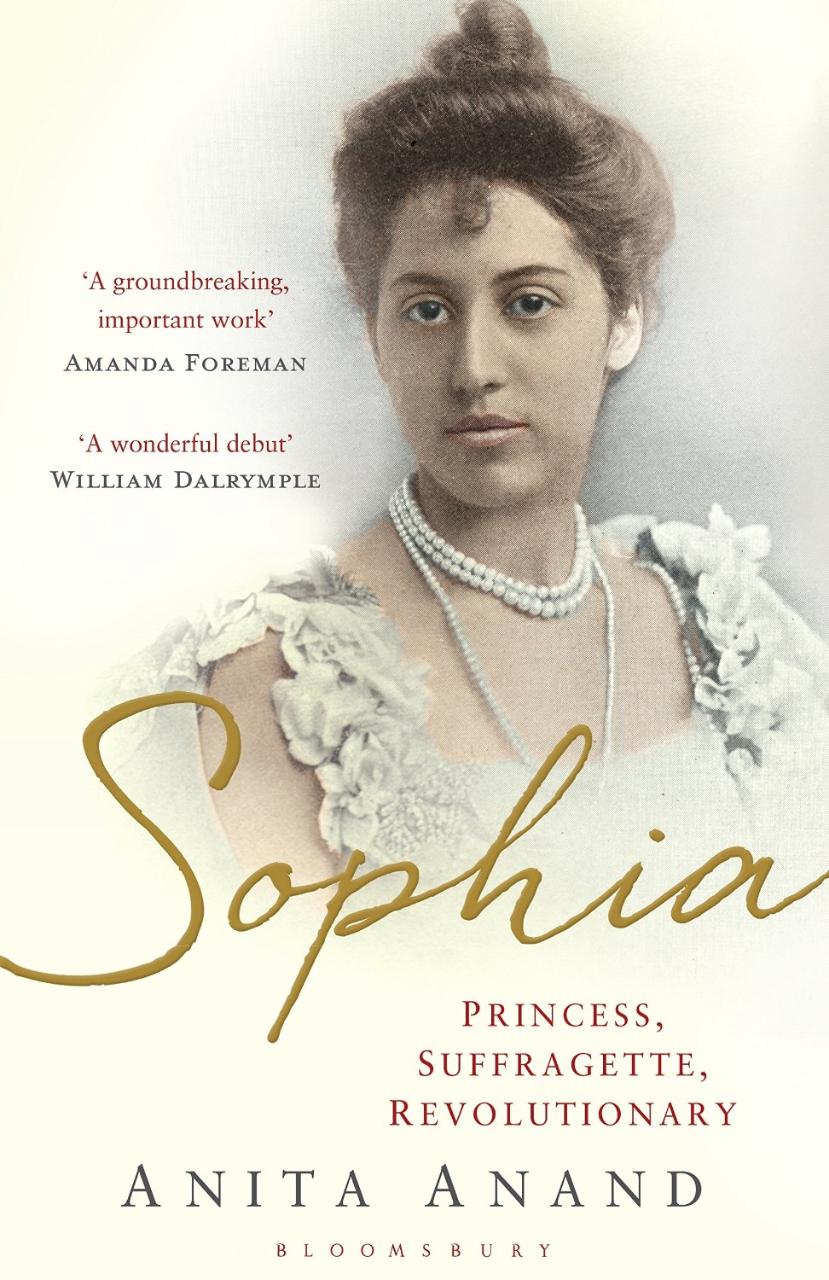

My book of the year is Sophia: Princess, Suffragette, Revolutionary by Anita Anand. Timed perfectly to coincide with the approach of the UK’s General Election, BBC journalist Anita Anand’s first book was an explosion of fascinating storylines all emanating from just one individual – Sophia Duleep Singh. Sophia is a biographer’s dream: god daughter to Queen Victoria, socialite, suffragette, anti-imperialist activist and World War One nurse – to name just a few of her life identifiers. Given such titles, the biggest surprise when reading the book is that more hasn’t been written about Sophia until now.And yet it hasn’t, which Anand also admitted was a great – and no doubt welcome – surprise. It must have also been an impediment as trying to move beyond the barebones of someone’s life and spin it into several hundred pages is no easy feat. Anand should therefore be double congratulated for overcoming this hurdle and creating an enjoyable read in the process. One fact unearthed is that Sophia was actually the suffragette movement’s most generous donor, though she never received the same level of fame as other high profile suffragettes, in part because she wasn’t arrested (the authorities wanted to avoid that for fear they would turn her into a martyr). At least through Anand’s book such facts are finally given airtime.

*This year we gave writers the option to tell us about the best book they read this year, and for this reason, some titles which appear in this feature were published before 2015.

What were your best books in 2015? Did we miss your favourites? What would you recommend to others?