by Alia Raffia

It was during a family trip to the magical city of Lahore aged fourteen that I fell in love with Mughal art. My brother and I went on adventures together and visited places like Lahore Fort, Shalimar Gardens and Wazir Khan Mosque as well as the streets of the old city. The freedom of exploring alone made it so much more special, and I fell in love with the city and its history and heritage. I felt a bond and a connection that I have never been able to let go of since.

The Mughal Empire spanned across modern-day India, Pakistan, and Afghanistan between1526 and 1858. At the time, the Mughals were the most powerful economic force in the world. It is estimated that Emperor Abkar’s net worth at his peak would translate to a staggering $21 trillion today, with control over 25% of the world’s GDP! Money was generously diverted to the arts and artists thrived under the Mughal rulers.

Mughal art included lavish architecture as well as immaculately manicured gardens and poetry which has influenced artists all over the world. Artists such as Rembrandt have featured unlikely subjects such as Mughal emperors Jahangir, Shah Jahan, and Aurangzeb. Rembrandt’s paintings are believed to be based on Mughal works of art brought to Amsterdam by the Dutch East India Company, which began trading in India in 1604.

Urdu poetry or shairi as we recognise it today took its shape in the 17th century when Urdu was declared the official language of the Mughal court. Urdu is arguably the most romantic language of the Indian subcontinent. Acoustically, it is light and lilting, delicate on the ears and sophisticated even in simple sentence constructions. When expressed with skill in Urdu, the complexity and nuance of an emotion deepens. It is the language of love and poetry. Urdu shairi is based on a system of measure, and has a very rigid form. There are several types of Urdu shairi, one of which is the hugely popular ghazal. Ghazal literally means “to talk to/about women”.

Traditionally, ghazals mainly deal with the topic of love, more specifically, unattainable love. The poet is the distraught, spurned lover who tries to gain the affection of an aloof or sometimes cruel beloved. Each verse of a ghazal is a complex but complete description of the topic. It requires great skill on the part of the poet to reduce the most complex of emotions into the fewest of words while maintaining the sophistication of thought and word. Books containing verses of poetry were often accompanied by Mughal miniature art.

I was was fourteen when I drew my first ever miniature with pencil crayons and watercolour paint, using a tiny picture printed in Dawn newspaper as inspiration. When I showed my grandmother in the morning she loved it and would ask me to present the picture to any of our relatives we came across. My grandmother’s and mother’s encouragement inspired me to continue.

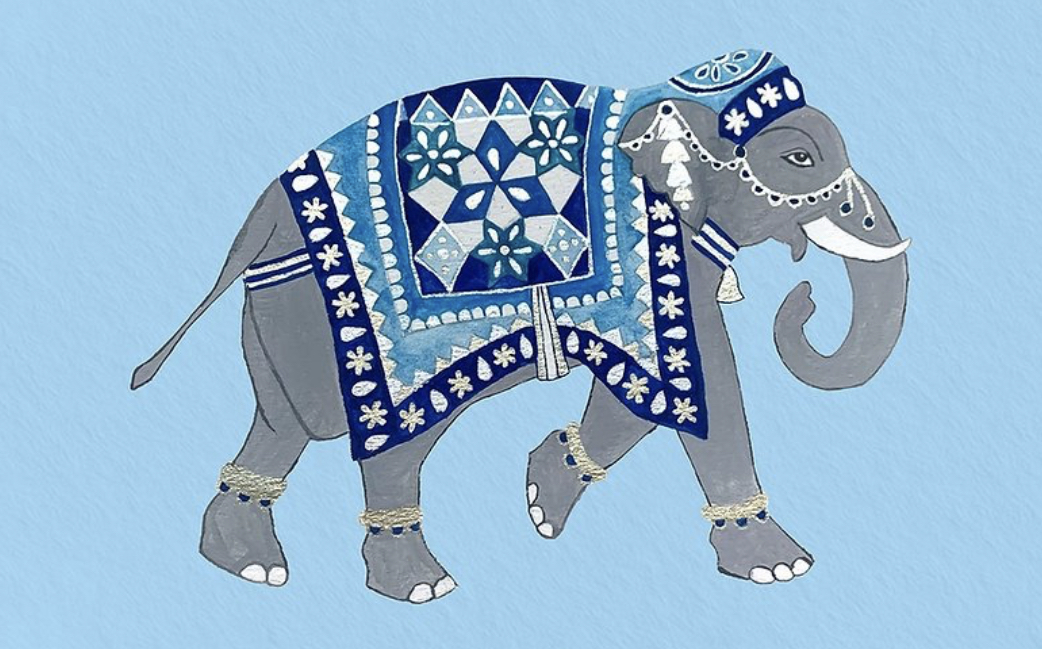

I took GCSE art and my work was heavily influenced by Mughal heritage and history. I painted miniatures inspired by imaginary landscapes, including a spectacular Mughal elephant.

Although I excelled at art GCSE unfortunately at A Level my work was critiqued as being too ethnic and I struggled. I could not let go of my passion for my heritage. I decided not to further my education with practical art as I felt that it was being marginalised.

I decided I wanted to change and influence art and culture. I wanted to understand the theory behind heritage and culture and who makes decisions as what is regarded as art and why. I completed my BA in Heritage Studies at the University of Manchester and subsequently went on to complete an MA in Art Galleries and Museum Studies. I now work at Manchester Museum. It is wonderful to be in an environment where I can express my heritage and identity. I have a long-term commitment to museums and heritage and hope I can make them relatable to so many more people in the future.

I have always loved museums and I find it fascinating that so much of South Asian culture and history is in collections in stores of museums across the world, which is unknown to many. Museums in the UK, USA and across Europe have huge collections of Mughal miniatures, textiles and artefacts in their collections as a consequence of empire and colonial history. I intend to raise the profile of this in the future and highlight museums that have Mughal art and artefacts in their collections. I am particularly interested in how they were acquired and their provenance.

I hope to revive the tradition of Mughal art and heritage, making it relevant to people today. It definitely still influences South Asian culture, from food, music, film and fashion, but I hope to bring the visual arts into the mainstream. I really believe with the rise of social media and online platforms culture is democratised. Museums and galleries can no longer be the deciders of what art is and art cannot be seen only in those spaces, the market can be dictated by the public. People can decide what art they wish to consume and I love that. I love engaging with people all over the world online about my work and I hope a new movement of art emerges as a consequence. I launched my website over the summer so it is very new but very exciting! I am going to be launching a series of YouTube videos soon that talk about museums and Mughal art and history in the next few weeks.

Alia Raffia is a Mughal Miniature artist and museum professional based in Manchester, UK. When she is not painting or in a museum or gallery, Alia sews and creates outfits inspired by her art. She is passionate about cultural heritage, ethical fashion and actively campaigns against modern-day slavery. You can see more of her artwork online at Alia Raffia Art.