Forty years may have passed since her ground-breaking report, The Art Britain Ignores, and yet it’s ‘extraordinary’ that the issues around diversity and the arts remain as ‘sharp, troubling and vibrant as ever,’ Naseem Khan has said.

The comments were made during her opening address delivered at Curve Theatre’s ‘Diversity in British Theatre’ conference, which marked the anniversary of the publication. Khan acknowledged that there has been huge change in British theatre since, but there was no time for complacency. In post-Brexit Britain, when the politics of our time seem to divide us all, Khan believes ‘The arts can play a crucial role in promoting diversity in the UK.’

The conference, devised by Curve in partnership with local BAME-led organisations Serendipity Arts and Inspirate, sought to look at the impact of the report and examine how far UK theatre has progressed since.

It was playwright Roy Williams’ keynote that set the tone of the day and inspired theatre-makers to ‘believe and trust, then do’. BAME writers must be allowed opportunity and freedom if they are to thrive. What might such an environment look like? Williams’ suggests it is one that doesn’t merely tick boxes, that doesn’t workshop new writing to the point of overkill, that doesn’t scrutinise or assume what black writing is about. ‘Black storytelling,’ he asserts, ‘can be about anything.’

‘The only limitation of being called a black writer is being expected to write about what others consider black work.’ Roy Williams, playwright

The morning panel on commissioning was the most compelling. The barriers for BAME writers to present their work on stage are more prevalent than ever before. The difficulties new writers face to breakthrough lies in part with the system. Funding cuts mean that there is little opportunity for new writers to build relationships with regional theatres. The disappearance of black theatre companies means there is less space to develop and find your voice outside of the mainstream.

But once in, it doesn’t get any easier. Playwright Emteaz Hussain who is currently on commission at BBC 3 and The Royal Court talks candidly about her experience of navigating the commissioning process and the internal struggle that comes with the territory. ‘Being understood is hard.’ Learning the language helps, she says, before doing an impromptu performance of her poem ‘I am an enigma’ – which reflects the self-talk required to get her through the process.

‘How do you manage the conversation when it’s the power structures that so often render you invisible?’ Emteaz Hussain, playwright

‘We treat new playwrights badly,’ Kerry Michael, artistic director at Theatre Royal Stratford East, admits. ‘If you’re a writer of colour, you’re emerging for a long time.’ The truth is plenty of new writing never makes it past development stages. There is an assumption that new writing won’t bring in audiences. This is problematic for theatres who are seeking to diversify: how can you reach new audiences when you don’t take risks on new voices?

Among the day’s well-meaning platitudes emerges a voice that is probably more reflective of the industry than the attendees in the room. It belongs to a white, male and middle class casting director who suggests that the real problem lies within the BAME community. He believes we aren’t doing enough to nurture artistic talent. ‘Where are you looking?’ shouts an angry voice from the stalls.

In the final panel, Cassandra Chadderton, head of UK Theatre encourages theatre-makers to give BAME artists space, to put on work on the main stages, not just in the studio. I can’t recall the last time I saw a piece of new writing by a BAME writer given such an opportunity. Something tells me, it would be a great place to start. Finally, there appears to be some hope that things will change, that the power imbalance that currently prevails and holds back marginalised voices will shift.

‘One day conferences like this won’t be needed,’ Williams said at the start of the day. We seem to talk about diversity, but very little appears to change. Part of the problem it seems, is the format of conferences themselves. Too often, they are clunky and overwhelming. By the time the panels are over and done with, everyone is too exhausted to move the discussion forward. There is too little time and energy left to share ideas, to agree to a set of action points to make much-needed changes. But change we must. If British theatre is to remain relevant with audiences it must truly reflect the society we live in. For that, we need to allow new voices to take centre stage.

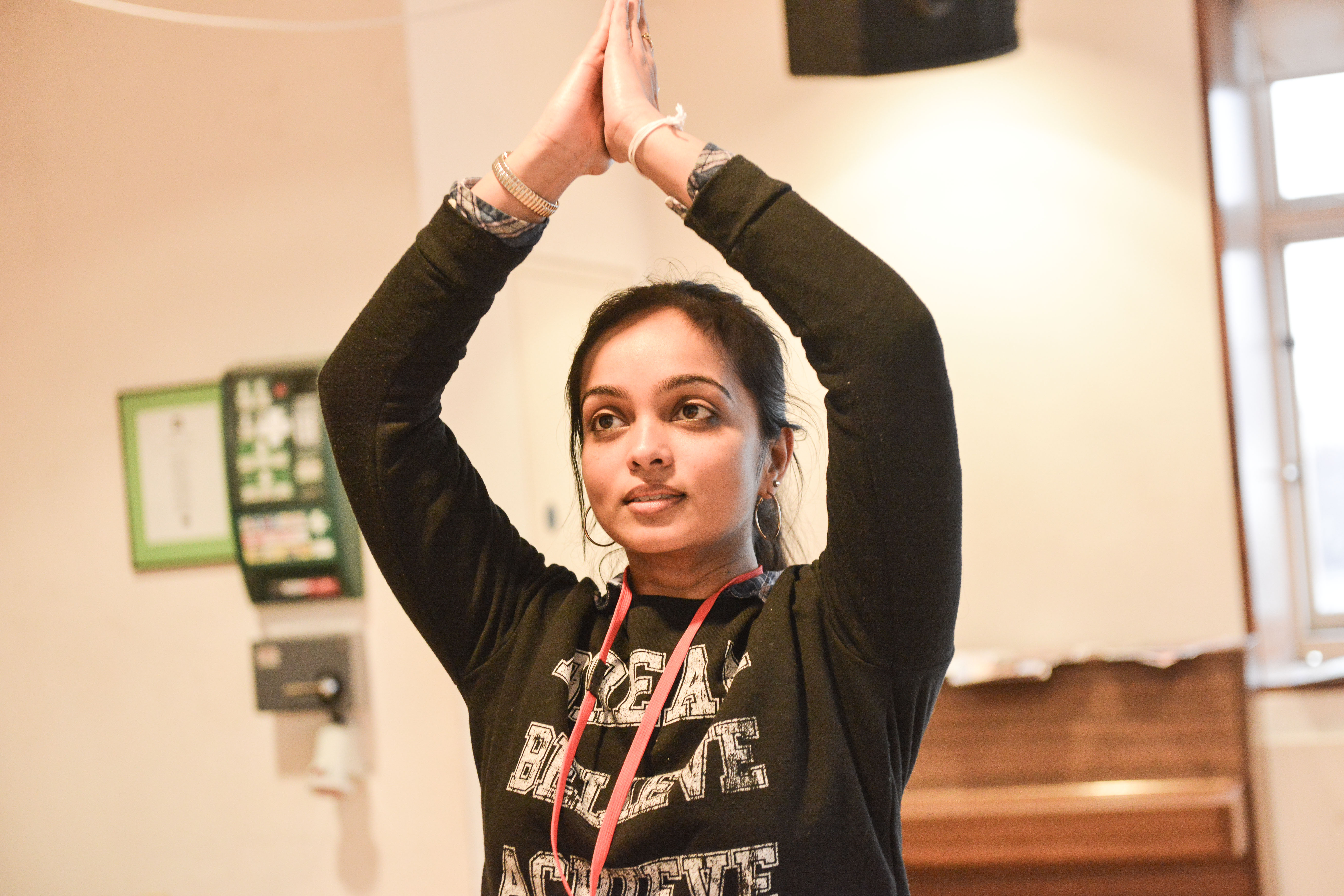

Image credit: Akram Khan’s Until the Lions at Curve Leicester on Nov 5.